Broken Pots and Broken People: How Kintsugi Became A Philosophy of Self Help (And What It Really Means)

Many of us walk around feeling a bit broken. Some of the time, anyway. So no wonder we are attracted to the idea of chipped pottery that is mended not with ordinary glue but with gold. A pot whose cracks are not hidden away but highlighted by precious metals seems to offer hope to the shattered. It feels like a metaphor of resilience.

A year ago, on a rainy morning in Tokyo, I booked myself into a ‘kintsugi workshop’ to learn some of the Japanese art of mending broken ceramics with precious metals. Kintsugi means ‘joining with gold’. Rather than trying to conceal the break in the china, it is displayed forever like a beautiful metallic scar. The idea of kintsugi is related to the Zen Buddhist concept of wabi or wabi-sabi: an acceptance that everything is imperfect and transient and that there is beauty in this imperfection, an idea promoted by tea masters in the sixteenth century. One of them, Furuta Oribe (1543–1611), once said that ‘perfect tea bowls are dull ones’.

A year ago, on a rainy morning in Tokyo, I booked myself into a ‘kintsugi workshop’ to learn some of the Japanese art of mending broken ceramics with precious metals. Kintsugi means ‘joining with gold’. Rather than trying to conceal the break in the china, it is displayed forever like a beautiful metallic scar. The idea of kintsugi is related to the Zen Buddhist concept of wabi or wabi-sabi: an acceptance that everything is imperfect and transient and that there is beauty in this imperfection, an idea promoted by tea masters in the sixteenth century. One of them, Furuta Oribe (1543–1611), once said that ‘perfect tea bowls are dull ones’.

Even if you are not familiar with the ins and outs of kintsugi, you’ve probably seen examples of it around in modern culture, because it is everywhere. In the West, kintsugi has become a spiritual metaphor for personal resilience and embracing your imperfections rather than being ashamed of them. Kintsugi is there in a Lana del Rey song and in the Star Wars films (Kylo Ren’s broken mask is mended kintsugi-style with glowing red glue). There are kintsugi blogs and kintsugi podcasts about using the idea of gold-fixed china as a branch of ‘wellness’.

I started researching kintsugi for my book THE HEART-SHAPED TIN (which is about the emotional life of kitchen objects, told through my own stories and those of others). I was aware that kintsugi had become a huge cultural phenomenon and wanted to find out more about what it actually means in Japan. (The technique of mending in gold has also been used for centuries by ceramicists in China and Korea; in the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge earlier this year, I saw these beautiful examples of Korean gold-mended celadon from the 1100s).

But I can’t deny that I had my own personal reasons for being interested in kintsugi as well. My partner was in Japan for work and I had flown out to join him for a week. Gold and silver became one of the themes of our brief time in Japan together. On a flying visit to Kyoto, we tried to visit the famous golden temple (Kinkaku-ji), the one that is listed as must-see in all the guidebooks, but neither of us has much sense of direction and we got on the wrong bus and ended up at the smaller and less touristy silver temple instead (Gingaku-ji). It was a brilliant mistake, as it turned out. The garden of the silver temple was one of the most calm and beautiful places either of us had ever been.

The teacher of the kintsugi workshop, a young woman called Aya Oguma, supplied us with a range of aesthetically pre-broken cups to choose from. Kintsugi has become so popular that people do not necessarily wait for a utensil to break before having a go at it. Aya told us that demand for kintsugi had soared among their local customers because the craze for kintsugi outside Japan has given the Japanese themselves a renewed appreciation for it.

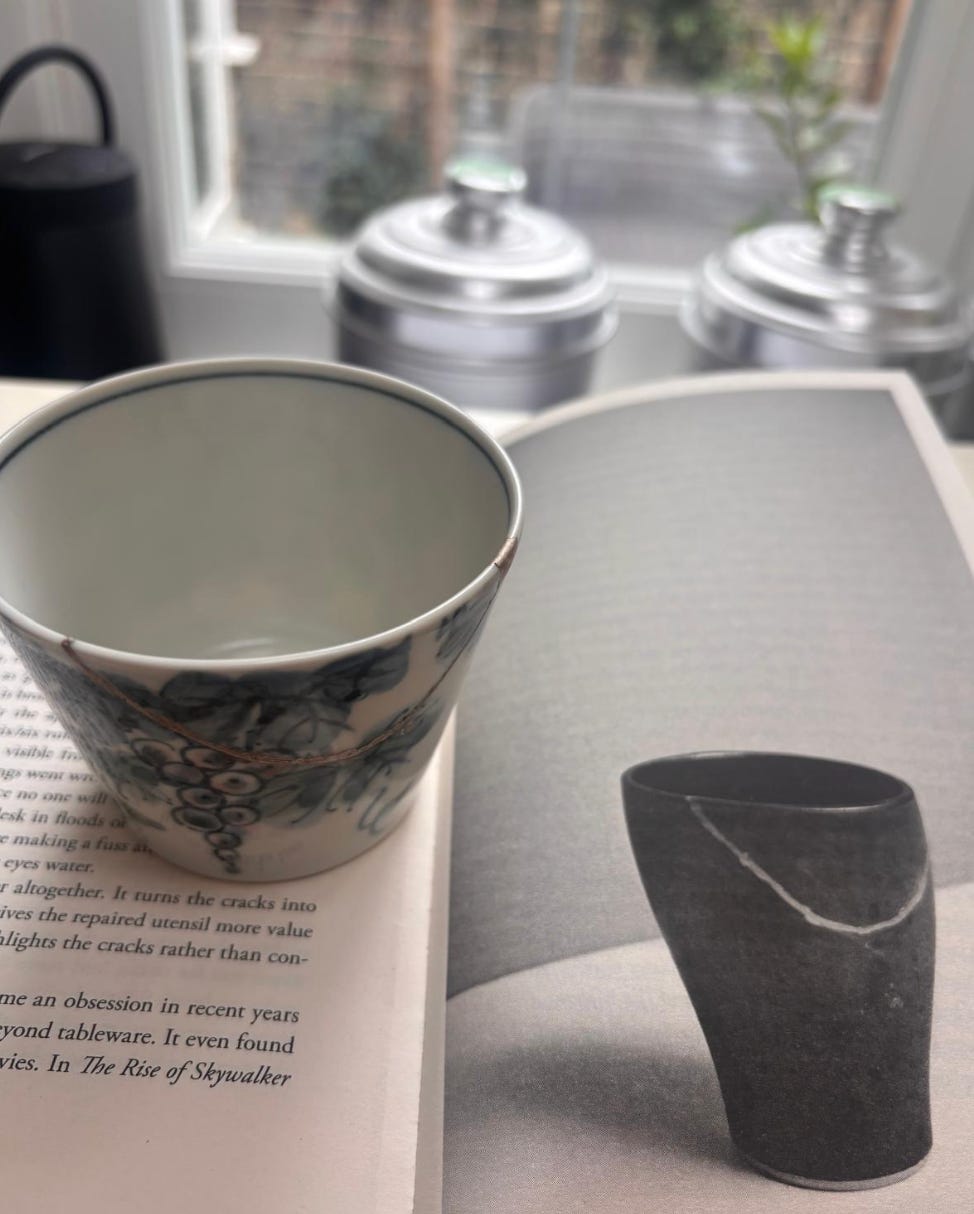

I chose a blue and white cup which I decorated with silver (technically, my cup should have been called ‘gintsugi’ not ‘kintsugi’ because kin is gold and gin is silver). He chose a plain black cup and decorated it with gold. We learned how to apply urushi – the sap of the lacquer tree – to our broken cups using tiny paintbrushes before sticking the pieces back together like a jigsaw puzzle and then applying the metal powder with a brush and a piece of silk wadding. The cups were eventually put into wooden boxes so that the adhesive could ‘cure’ for a week. Although this was a slow process, it was much faster than true traditional kintsugi, in which it may take many months to mend a single item.

Sitting side by side mending our cups, I couldn’t help feeling that this act of repair might have wider meaning for us as two divorced people. It was only the faultlines in our past that allowed us to be together. My absurd good fortune in finding this new life after the sadness of separation made me think of a line from Great Expectations by Dickens. ‘I have been bent and broken but – I hope – into a better shape.’ So yes, I am a sucker for the idea of imperfect cups whose scars are golden.

But are we wrong to think of kintsugi as an optimistic branch of self-help? The more I learned of kintsugi both from Aya and from my subsequent research, the more I saw that it wasn’t really the individualist and upbeat idea that it has sometimes been taken for in the West. Aya – who trained in kintsugu repair with a master craftsman after the end of her marriage – emphasised that true kintsugi in Japan didn’t have the ‘spiritual’ wellness meanings it has recently been given .

Kintsugi is actually more a collective idea than an individual one. It’s about paying due respect to the objects in our lives. Kintsugi is sometimes mistaken for a ‘go-with-the-flow’ attitude to breakage but Aya explained to us that kintsugi was linked to the Japanese concept of mottainai which implies the desire to waste nothing. Mottainai carries a sense of heavy regret and duty for objects that are not handled with due reverence. Gods are found everywhere in Shinto religion from the sun and the moon to every grain of rice and household objects. Aya said that when she taught kintsugi to Japanese customers, they were less likely to talk about human scars and more likely to talk about how they couldn’t bear to throw away a family memento even if was damaged. Kintsugi was less about them and more about the objects.

I was still a little puzzled as to how kintsugi expresses a desire to waste nothing. If simplicity and frugality is the goal, wouldn’t simple glue suffice? Why go to the expense of gold? I write more about the history of kintsugi in THE HEART-SHAPED TIN and how it emerged from fusing together two contradictory movements. On the one hand, there was the frugal philosophy of the tea masters who praised broken china as more interesting than intact china. On the other hand, there was an artistic movement called maki-e : a new and lavish artistic movement for the wealthy in which gold was sprinkled on almost anything, from buildings to furniture to plates.

Kintsugi is not about denying that it’s sad when something breaks; rather it’s a way to honour and memorialise that sadness. Mending something with gold is a kind of overkill, reflecting the torrent of emotion that can be unleashed when a treasured possession breaks – or, in the case of the 2011 earthquake in Japan, when thousands of people lost every last thing in their house.

Some have explained the undimmed appeal of kintsugi in Japan through the country’s history of earthquakes. In her book Kintsugi:The Poetic Mend (2021), artist Bonnie Kemske notes the Japanese saying: ‘Everything that has a shape, breaks.’ Cracks and fault lines are part of the scenery in Japan in a way that is not true in most other countries.

In 2011 Japan suffered the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the country, triggering a tsunami in which around 20,000 people died and thousands more lost their homes and all their possessions. A kintsugi teacher called Nakamua Kunio started holding kintsugi workshops in the worst-affected areas of the country. ‘I realised we needed to repair ourselves, to remake things,’ he said. He used a mixture of silver and brass powder, rather than gold, to make his kintsugi workshops more affordable.

I was left feeling that kintsugi is a much more poignant set of ideas than it is allowed to be in the West. Most lost things and people are beyond our control to resurrect. But to mend a pot or a cup and make it shinier and stronger than before is a small, possible action.

Kintsugi won’t save us from being broken because sometimes, nothing can. One of the things that stayed with me long after we had finished the kintsugi workshop and were once again at home, drinking tea from our respective cups in our separate homes, was a story that Aya had told us about a man who lost his wife.

After his wife’s death, this man brought in some of her pottery to be mended. Aya was so moved,to see the look on his face after she presented him with the pottery after its kintsugi restoration. No-one could bring back his wife but this gold-mended china was a new way to honour her spirit: a glowing shrine that he could hold.